January 16, 2018 From rOpenSci (https://deploy-preview-121--ropensci.netlify.app/blog/2018/01/16/tidyhydat/). Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under the CC-BY license.

One of the best things about learning R is that no matter your skill level, there is always someone who can benefit from your experience. Topics in R ranging from complicated machine learning approaches to calculating a mean all find their relevant audiences. This is particularly true when writing R packages. With an ever evolving R package development landscape (R, GitHub, external data, CRAN, continuous integration, users), there is a strong possibility that you will be taken into regions of the R world that you never knew existed. More experienced developers may not get stuck in these regions and therefore not think to shine a light on them. It is the objective of this post to explore some of those regions in the R world that were highlighted for me when the tidyhydat package was reviewed by rOpenSci.

tidyhydat is a new rOpenSci R package that provides a standard method of accessing Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Water Survey of Canada data sources (WSC) using a consistent and easy to use interface that employs tidy data principles. I developed the package because I was repeating the same steps to import and tidy WSC data in R. Many useRs will read this post and think “I’d know how to do that”. To you I tip my hat. To those who read this and think “huh, never knew that”, you are the target audience. In this post, I’ll focus on 5 things that I learned during the tidyhydat rOpenSci review, provide a brief introduction on how the package works and provide an example use case.

tidyhydat can be installed from CRAN by the usual manner:

install.packages("tidyhydat")

Five things

Five things

1. Documentation

1. Documentation

A second and third set of eyes, in the form of rOpenSci reviewers, on the tidyhydat documentation added to the quality of the package immensely. It is so easy to write documentation that makes sense when you are writing the code, and makes zero sense to anyone else. Having reviewers review documentation and politely tap you on the shoulder to say “this is barely English” is the clear line between a package that is useful to only you and a package that is useful to others. From adding examples to each and every function, to suggestions that units be included in function documentation, all provide a more clear pathway for a potential new user to navigate the package.

2. Where to store external data

2. Where to store external data

The single biggest feature of tidyhydat that caused the most headaches and learning opportunities for me is the fact that much of its capabilities rely on an external .sqlite3 data: HYDAT. HYDAT is the WSC’s quarterly published archive of hydrometric data. Some stations data range extends into the 19^th^ century. It is, however, rather messy data and in a format (.sqlite3) that is likely unfamiliar to many useRs accustomed to flat data files like .csv, .txt or .xlsx.

tidyhydat seamlessly removes the need for a user to ever deal with the .sqlite3 file directly except running a function to download HYDAT upon installation:

download_hydat()

Well, at least it does now. Previously, I had devised some convoluted solution that involved downloading the data to a specific directory then setting that directory in your .Renviron file. That is when one of the reviewers suggested the wonderfully simple rappirs package. As is so often the case, my internal dialogue of “wow, this is a cool package!” was followed by “and of course Hadley Wickham wrote it”. (Author’s note: does he sleep?). Here is the description of the rappdirs package:

An easy way to determine which directories on the users computer you should use to save data, caches and logs.

This is exactly what I needed. Via rappdirs::user_data_dir() I was able to specify a directory to download the database that is OS-independent then tell every hy_* function to look for HYDAT in that directory.

3. Prefix-style function naming

3. Prefix-style function naming

In addition to interacting with HYDAT, tidyhydat also provides a series of functions to import real-time hydrometric data into R. Initially, to distinguish real-time functions from those that access HYDAT, I employed a confusing scheme where HYDAT functions were capitalized (DLY_FLOWS) and real-time data functions were presented as lowercase (download_realtime). Luckily another helpful suggestion by a reviewer was to employ consistent prefix-style naming rather than capitalization to accomplish this. Along with a slight function name change, DLY_FLOWS() became hy_daily_flows(). This small change actually solves several problems at once:

- Prefixes act as sort of a package specific namespace helping to avoid any conflicts with other packages.

- Prefixes facilitate auto-completion because users only have to type

hy_(+ TAB) at which point they can choose the function they would like to use. - Enable a user to immediately know if a function accesses HYDAT. This unified interface provides clarity and consistency.

4. Vignettes that use external data on CRAN

4. Vignettes that use external data on CRAN

One reviewer suggested that a vignette which worked through a complete analysis may be useful to a new user. This was a great idea. One problem: Since the package was destined for CRAN it needed to meet all the associated requirements. With respect to long-form documentation CRAN does not build vignettes and only makes sure they are actually runnable; it uses what you’ve built locally. To run through an example analysis, I needed to access the HYDAT database which is not shipped to CRAN. This discussion provided a delightfully simple solution to my problem. The solution involved setting a global knitr option for eval as TRUE or FALSE depending on the presence of an environment variable. Locally when I build the vignettes, the environment variable is present so eval=TRUE. On CRAN, the environment variable is absent for eval=FALSE. Therefore the vignette code becomes runnable on CRAN.

5. An exercise in reproducible science.

5. An exercise in reproducible science.

tidyhydat was originally developed to save time accessing data. Instead of frequently opening database connections, making approximately the same query, forgetting to close the database connection, trying to reopen it, cursing R and generally blaming all the wrong people, I developed a package. However, after using the package it has become clear that it has a much deeper and useful feature — it is a tool that facilitates reproducible science and can provide reproducible workflows that support science-based decisions around water flow. It is now possible to set up code-based workflows that are re-runnable with more current data, different stations or regions over a range of time scales. The importance of this cannot be overstated and will be the focus of the remainder of this post.

A reproducible work flow

A reproducible work flow

To illustrate a reproducible workflow facilitated by tidyhydat and made possible by the capabilities of R, we can ask a simple question related to a hydrometric station: how unique is this station compared to others in the same watershed? In this example we will consider the FRASER RIVER AT MISSION station. Records extend over many years and we can compare an overlapping record using correlation to develop a measure of uniqueness for this station. But first we need to engage in some preamble:

Required packages

Required packages

A portion of the package audience is likely those with little or no experience in R so an example of the type of analysis possible with tidyhydat is helpful. For our purposes here, we need to install a whole other slew of packages. The packages needed for this analysis mostly fall into either the tidyverse collection of packages or the igraph family of packages. Several of these packages (dplyr, tidyr) were already installed alongside tidyhydat. The remaining packages can be installed using:

install.packages(c("purrr","corrr","igraph","ggraph","ggmap"))

then load the required packages:

library(tidyhydat)

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

library(corrr)

library(igraph)

library(ggraph)

library(ggmap)

Using tidyhydat

Using tidyhydat

The first step when using tidyhydat will often start with the hy_stations() function which holds metadata for all stations (active or discontinued) in HYDAT. WSC has a standard 7 digit station number format which contains hierarchical watershed information. The FRASER RIVER AT MISSION (08MH024) is located in the sub-sub-drainage Lower Fraser - Nahatlatch (08MH), in the sub-drainage Lower Fraser (08M) in the Pacific Ocean drainage (08). We can leverage that embedded watershed information and generate a list of station ID’s for all stations within our example watershed the Lower Fraser - Nahatlatch (08MH). An English description of the code below would follow as “Extract all stations from HYDAT then extract the first four digits from STATION_NUMBER then filter for some sub-sub-drainage, then filter the stations for those that are active, then extract the station number as a vector”:

daily_flows_boxed <- hy_stations() %>%

mutate(SUB_SUB_DRAINAGE_AREA_CD = substr(STATION_NUMBER, 1,4)) %>%

filter(SUB_SUB_DRAINAGE_AREA_CD == "08MH") %>%

filter(HYD_STATUS == "ACTIVE") %>%

pull(STATION_NUMBER)

daily_flows_boxed

## [1] "08MH001" "08MH002" "08MH005" "08MH006" "08MH016" "08MH024" "08MH029"

## [8] "08MH035" "08MH056" "08MH076" "08MH090" "08MH098" "08MH103" "08MH126"

## [15] "08MH141" "08MH147" "08MH149" "08MH152" "08MH153" "08MH155" "08MH156"

## [22] "08MH166" "08MH167" "08MH168"

To move from the station vector to daily flow information we simply add another tidyhydat function hy_daily_flows() to the pipe:

daily_flows_boxed <- hy_stations() %>%

mutate(SUB_SUB_DRAINAGE_AREA_CD = substr(STATION_NUMBER, 1,4)) %>%

filter(SUB_SUB_DRAINAGE_AREA_CD == "08MH") %>%

filter(HYD_STATUS == "ACTIVE") %>%

pull(STATION_NUMBER) %>%

hy_daily_flows()

daily_flows_boxed

## # A tibble: 320,307 x 5

## STATION_NUMBER Date Parameter Value Symbol

## <chr> <date> <chr> <dbl> <chr>

## 1 08MH005 1911-10-01 Flow NA <NA>

## 2 08MH006 1911-10-01 Flow NA <NA>

## 3 08MH005 1911-10-02 Flow NA <NA>

## 4 08MH006 1911-10-02 Flow NA <NA>

## 5 08MH005 1911-10-03 Flow NA <NA>

## 6 08MH006 1911-10-03 Flow NA <NA>

## 7 08MH005 1911-10-04 Flow NA <NA>

## 8 08MH006 1911-10-04 Flow NA <NA>

## 9 08MH005 1911-10-05 Flow NA <NA>

## 10 08MH006 1911-10-05 Flow NA <NA>

## # ... with 320,297 more rows

Now that we have all our hydrometric data tidy and in R, I’ll outline a cool example of what you can do with it.

Correlate all stations in Fraser River - Lower Nahatlatch (08MH)

Correlate all stations in Fraser River - Lower Nahatlatch (08MH)

Remember, we are trying to evaluate the uniqueness of the FRASER RIVER AT MISSION via correlation as compared to other stations in the watershed. We can utilize the excellent corrr package, specifically correlate() and stretch(), to calculate the correlation between each station all in a pipe. This series of piped functions takes all the daily flow data (daily_flows_boxed), converts it to long format, removes the columns we don’t want, correlates each column, stretches the data into long form and gets rid of correlations that results in NA’s:

cor_df <- daily_flows_boxed %>%

spread(STATION_NUMBER, Value) %>%

select(-Date, -Symbol, -Parameter) %>%

correlate() %>%

stretch() %>%

filter(!is.na(r))

igraph munging

igraph munging

At this point we need to begin using the igraph package for network analysis. Our first step is to make a graph for all the correlations then construct a subgraph for only the 08MH024 station:

## Convert to an igraph object for plotting

graph_correlation <- graph_from_data_frame(cor_df)

## Subset for those edges from 08MH024

graph_sub <- subgraph.edges(graph_correlation, E(graph_correlation)[inc('08MH024')])

Create plot

Create plot

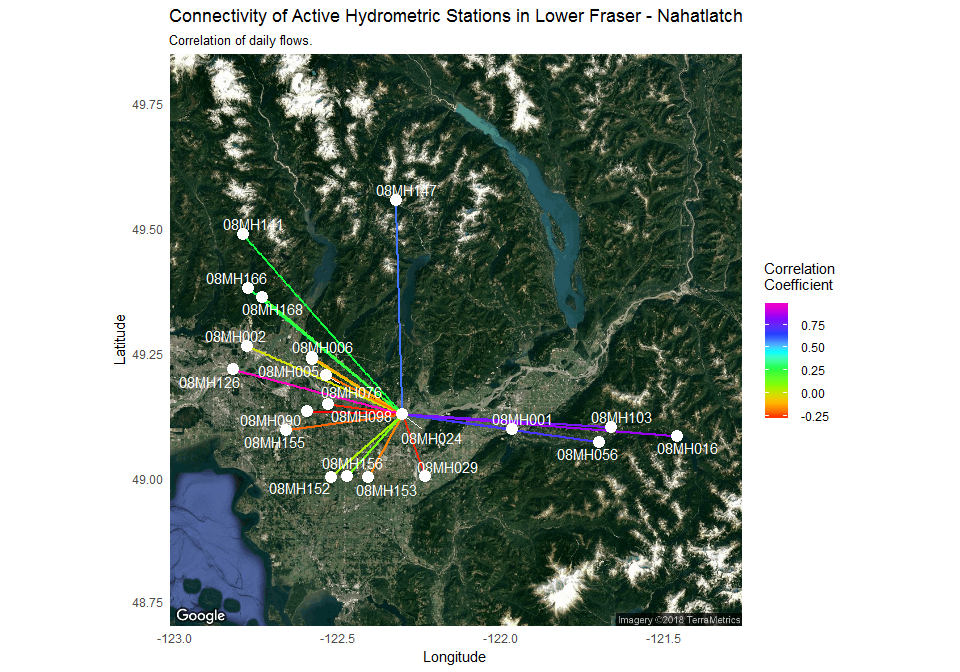

Finally, our last step is to plot each point in a spatially accurate manner and apply the results from the igraph object. The plotting step graphs the station location against satellite imagery using the ggmap and ggraph packages and connect stations with coloured lines that reflect the strength of the correlation:

## Get the lat long data, isolate the coordinates and rename to x and y

latlong_layout_ggmap <- hy_stations(station_number = V(graph_sub)$name) %>%

select(LONGITUDE, LATITUDE) %>%

rename(x = LONGITUDE, y = LATITUDE)

## Create the spatial layout based on latitude and longitude.

spatial_layout_ggmap <- create_layout(graph = graph_sub,

layout = "manual",

node.positions = latlong_layout_ggmap)

## Acquire the static map

map <- get_map(c(min(latlong_layout_ggmap$x),

min(latlong_layout_ggmap$y),

max(latlong_layout_ggmap$x),

max(latlong_layout_ggmap$y)),

source = "google", maptype = 'satellite', zoom = 9)

## Plot the igraph object

ggmap(map, base_layer = ggraph(spatial_layout_ggmap), device = "extent") +

geom_edge_link(aes(color = r), edge_width = 1) +

guides(edge_alpha = "none") +

scale_edge_colour_gradientn(name = "Correlation \nCoefficient", colours = rainbow(8)) +

geom_node_point(colour = "white", size = 4) +

geom_node_text(aes(label = name), repel = TRUE, colour = "white") +

theme_minimal() +

labs(y = "Latitude", x = "Longitude",

title = "Connectivity of Active Hydrometric Stations in Lower Fraser - Nahatlatch",

subtitle = "Correlation of daily flows.")

What does the plot tell us

What does the plot tell us

Our original objective was to assess if the 08MH024 station was a unique station. This type of plot provides a clear pattern of hydrologic linkages. Flows at 08MH024 are more similar to stations at higher elevations (e.g. 08MH016) and less similar to lower elevation stations (e.g. 08MH002) demonstrating a spatial pattern of uniqueness. This likely reflects the importance of upstream hydrologic processes. The Fraser River, the largest river in British Columbia drains a huge area (228000 square km) where the flows in the majority of contributing upstream tributaries are driven by snow melt. This station, however, is located near the coastal environment where river flow is driven more by rainfall. This helps us connect upstream and downstream processes and evaluates the relative contributions to flow in the main river. A visual tool, such as the one illustrated here, provides a clear example of using the capabilities of R after bringing in a rich hydrometric data set, and highlights a reproducible hydrological workflow in R.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank rOpenSci for the opportunity to have the tidyhydat package reviewed. From the package review side of things, I would like to thank Scott Chamberlain, Laura DeCicco and Luke Winslow for their time and efforts in improving the package. Hopefully this post has outlined the ways in which their contributions were useful. From the being awesome and helpful side of things, I also say thanks to Stefanie Butland for helping shepherd this package to rOpenSci. More generally tidyhydat offers another piece of evidence that the rOpenSci package review process consistently yields better results and returns more user friendly products that facilitate open science.